1. The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea by Yukio Mishima

2. Room by Emma Donoghue

3. Snow Country by Yasunari Kawabata

4. Guns, Germs and Steel by Jared Diamond

5. The Boy Next Door by Irene Sabatini

6. Lady Chatterley's Lover by D.H. Lawrence

7. Revolutionary Road by Richard Yates

8. The Book of Tea by Kakuro Okazawa

9. Let the Great World Spin by Colum McCann

10. What I Talk About When I Talk About Running by Haruki Murakami

11. Life of Pi by Yann Martel

12. A Wild Sheep Chase by Haruki Murakami

13. The Red Tent by Anita Diamant

14. Rabbit, Run by John Updike

15. Montana 1948 by Larry Watson

16. The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin

17. The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho

18. This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald

19. The Sound of Waves by Yukio Mishima

20. Tales of the City by Armistead Maupin

21. Sex and the City by Candace Bushnell

22. East of Eden by John Steinbeck

23. The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

24. Gift from the Sea by Anne Morrow Lindbergh

25. Small Gods by Terry Pratchett

26. LIAR by Justine Larbalestier

27. The Time Traveler's Wife by Audrey Niffenegger

28. Catching Fire by Suzanne Collins

29. Slouching Towards Bethlehem by Joan Didion

30. The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway

31. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Larsson

32. The Blue Castle by L.M. Montgomery

33. A Midsummer Night's Dream by William Shakespeare

35. Island beneath the Sea by Isabel Allende

36. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

37. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain

38. The Elements of Style by William Strunk Jr. and E.B. White

39. Holes by Louis Sachar

40. Mockingjay by Suzanne Collins

41. Nick and Norah's Infinite Playlist by Rachel Cohn and David Levithan

42. The Lake by Banana Yoshimoto

43. A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway

44. The Time of Their Lives by Al Silverman

45. Hogfather by Terry Pratchett

46. Notes from Underground by Fyodor Dostoevsky

47. The Niigata Sake Book by the Niigata Sake Brewers Association

48. Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe

49. Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

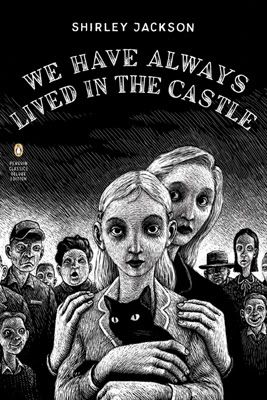

50. We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson

Some statistics:

- I read a total of 13566 pages

- 32 were by male authors; 18 were by female authors

- 27 were by American authors, eight were by Japanese authors, five were by British authors, three were by Canadian authors, two were by African authors (one Nigerian and one Zimbabwean), and one each were by Russian, Swedish, Australian, Brazilian and Irish authors. (Hey, I read at least one book from every continent!)

- The number of nonwhite authors I read is embarrassingly low. How low depends on what you consider nonwhite, but if we're talking people who actually face oppression (ie not Isabel Allende or Japanese from Japan), then I would count two. Yes, two. Something to focus on this year.

- 12 books were translated from other languages (mostly Japanese; also Spanish, Russian, Portuguese, and Swedish); the rest were written in English.

- 41 were fiction; 9 were nonfiction

- 41 were post-1950, five were written between 1900 and 1950, three were written in the 19th century, and one was written in the 17th century

- 32 were print books; 18 were ebooks

- I reread 3 books (This Side of Paradise, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Fahrenheit 451); the rest were new

- I read more than one book by the same author in six cases: Mark Twain (2 books), Ernest Hemingway (2 books), Suzanne Collins (3 books), Haruki Murakami (2 books), Yukio Mishima (2 books), and Terry Pratchett (2 books).

- My favorite books I read this year: Revolutionary Road, A Wild Sheep Chase, The Hunger Games, The Left Hand of Darkness, East of Eden, LIAR, Holes, and We Have Always Lived in the Castle.

So that concludes the challenge, I guess. I'm hoping to get back to writing about Japan here; I thought about continuing to blog about the books I'm reading by doing short summaries 5 to a post or so, but instead I think I want to start using Goodreads. One of my favorite parts of doing the book challenge (both this year and when I last did it in 2007) was tracking the books I read and being able to see what the breakdown was at the end of the year on genre, fiction vs. nonfiction, etc. I certainly don't need to read 50 books to do that, but it's the only time I've bothered to, so this year I'll try to keep doing it no matter how few or many books I read. Now that the challenge is over I'm letting myself read all the long books I've been putting off--I'm almost done with The Girl Who Played With Fire (which is fantastic) and next am going to read Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea. Excitement!